Labour shortages became a key issue for Australian farmers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Travel bans, border closures and quarantine issues wreaked havoc on the supply of seasonal workers. These shortages posed a challenge to both the profitability and sustainability of Aussie farms. The pandemic and associated border closures are now well and truly behind us. So how has labour availability improved since, which industries are still under strain, and how is labour availability expected to evolve in 2023?

The current state of seasonal labour in Australia

Australian agriculture is crucial to the economic prosperity of Australia. ABARES has forecast Australian farm production will reach $90 billion in value in 2022/23. Seasonal labour plays a key role in supporting the industry. It enables a timely and sustainable harvest of crops across a range of sectors. Border closures and travel restrictions have caused huge disruptions to the supply of labour over the last three years. The reopening of borders has helped improve things a great deal. This is due to the rebound in international and interstate travel, along with increased migration. The creation of a horticultural award also drove increased interest from workers. While these changes have been effective, the expansion of the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme has been the big driver used to tackle the labour crisis.

The reopening of borders drove many to assume seasonal labour shortages were a thing of the past. However, while the availability of labour has improved, sourcing workers remains a challenge. The different requirements of various agricultural sectors drive diverse requirements for seasonal labour. As a result, agricultural sectors have been affected by worker shortages in unique ways.

A bounty of fruit and vegetables, but a shortage of labour

Horticultural producers reported the most severe labour shortages during the pandemic. Fruit and vegetable production is particularly seasonal. It requires workers for intense, but relatively brief periods of time. We estimate well over $80 million worth of produce was lost due to a lack of seasonal labour during the pandemic. Many larger growers are turning to automated technology to reduce reliance on labour. This throws up its own challenges with cost being a key prohibitive factor. While in many cases the technology simply isn’t up to the task. The government has invested in expanding the PALM scheme to better address these shortages. The majority of workers available through the PALM scheme are now working on horticultural farms. This has helped to plug the significant gaps that emerged during the pandemic. While this scheme is continuing to grow, it remains an expensive option for producers. As a result, many growers, particularly smaller producers, continue to struggle to get crops off at ideal times.

Why shearers are the new rock stars of the Ag workforce

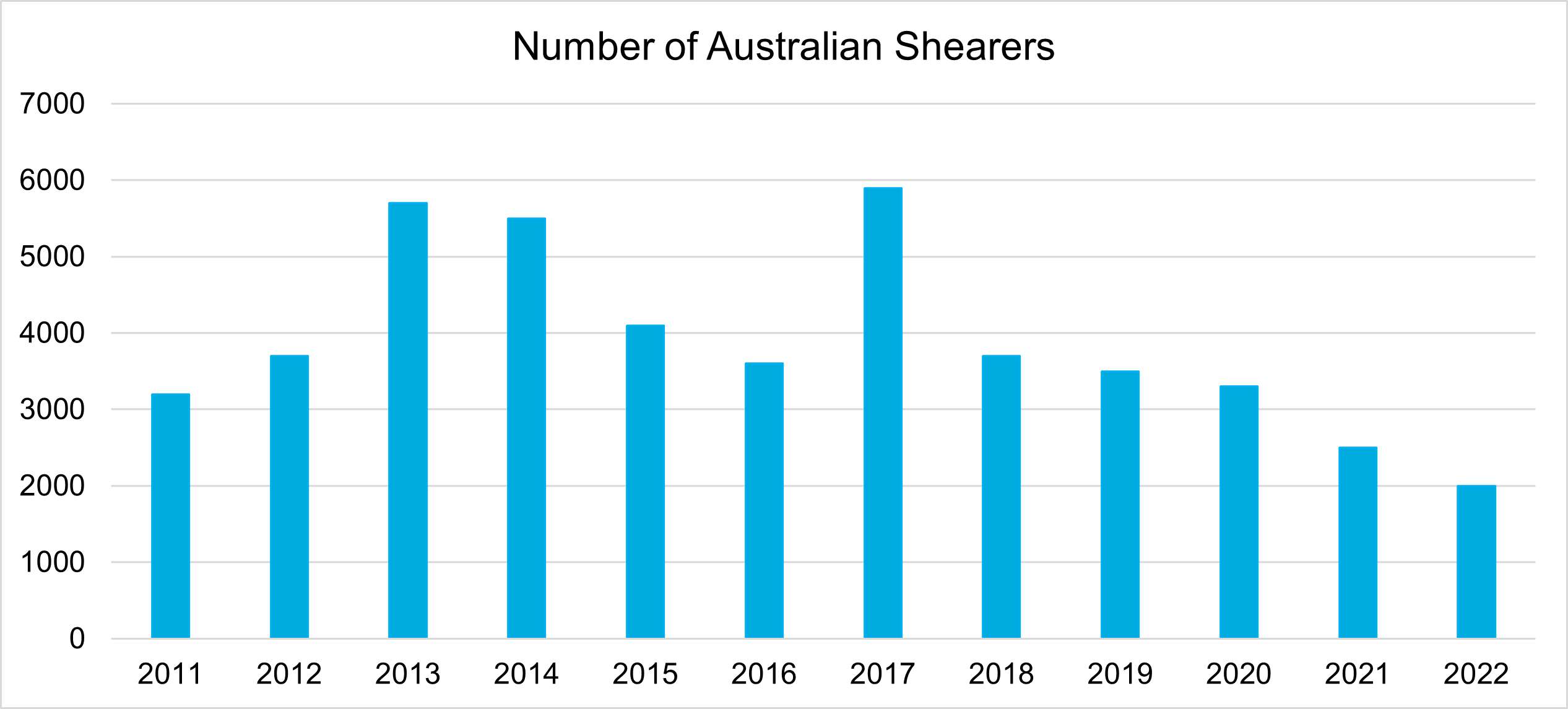

The wool industry is also struggling with shortages in 2023. Shearers remain in short supply despite the re-opening of borders. Australian Bureau of Statistics data estimates the number of local shearers dropped to just over 2000. The figure was five times that in 1990. These shortages have surprisingly worsened in 2023. A lack of new entrants into the industry has driven a skill related shortage. This has pushed the shearing cost per sheep much higher. Supply gaps have been further exacerbated by a large national flock following rebuilding over the past couple of seasons. Wet weather during spring also saw a large number of sheep held over for shearing in the autumn. This added extra sheep for shearing to the already large flock.

The skilled nature of the work also makes it more difficult to cover shortfalls. Increased migration from New Zealand will benefit the sector following the border re-opening. A deal between Australian and New Zealand to upskill shearers has come as welcome news. This will see Australian wool growers invest more than $10 million into shearer and wool handler training. Sourcing shearers via the PALM scheme hasn't been viable, with the program focused on other industries. As a result, shearer shortages will continue through the busy autumn period. There are also growing fears this could become an ongoing issue in coming seasons.

What about our crops and cows?

The impacts of COVID-19 were less visible on dairy and cropping sectors in comparison. Cropping and dairy operations typically utilise fewer overseas workers. While labour shortages were apparent across broadacre farms, this was due to the record production across the sector. A compressed harvest added further strain on the workforce. A smaller winter crop is forecast for 2023/24 which should see minimal worker shortages within the sector next summer.

Over two thirds of dairy producers have struggled with shortages according to recent surveys. Dairy Australia launched a local jobseeker site in an effort to fill shortages. This has been a successful campaign with an influx of applications over the past three months.

Why new visa rules are both solving and exacerbating labour shortages

The pandemic brought about a couple of key legislative changes. These will likely alter the make-up of seasonal labour over the longer term. The growing importance of the PALM scheme has seen the number of Pacific worker's surge. The scheme has grown from 8,000 workers in March 2020 to over 35,000 in 2023. This number is expected to continue growing over the next 12 months. The scheme now plays a significant role in ensuring the availability of labour. While reports of an increase in the number of PALM workers absconding has been reported. The issue of absconding is now being addressed at a government level. The scheme will likely be further expanded to focus on a wider variety of sectors. However, there are no firm timeframes as to when this would occur.

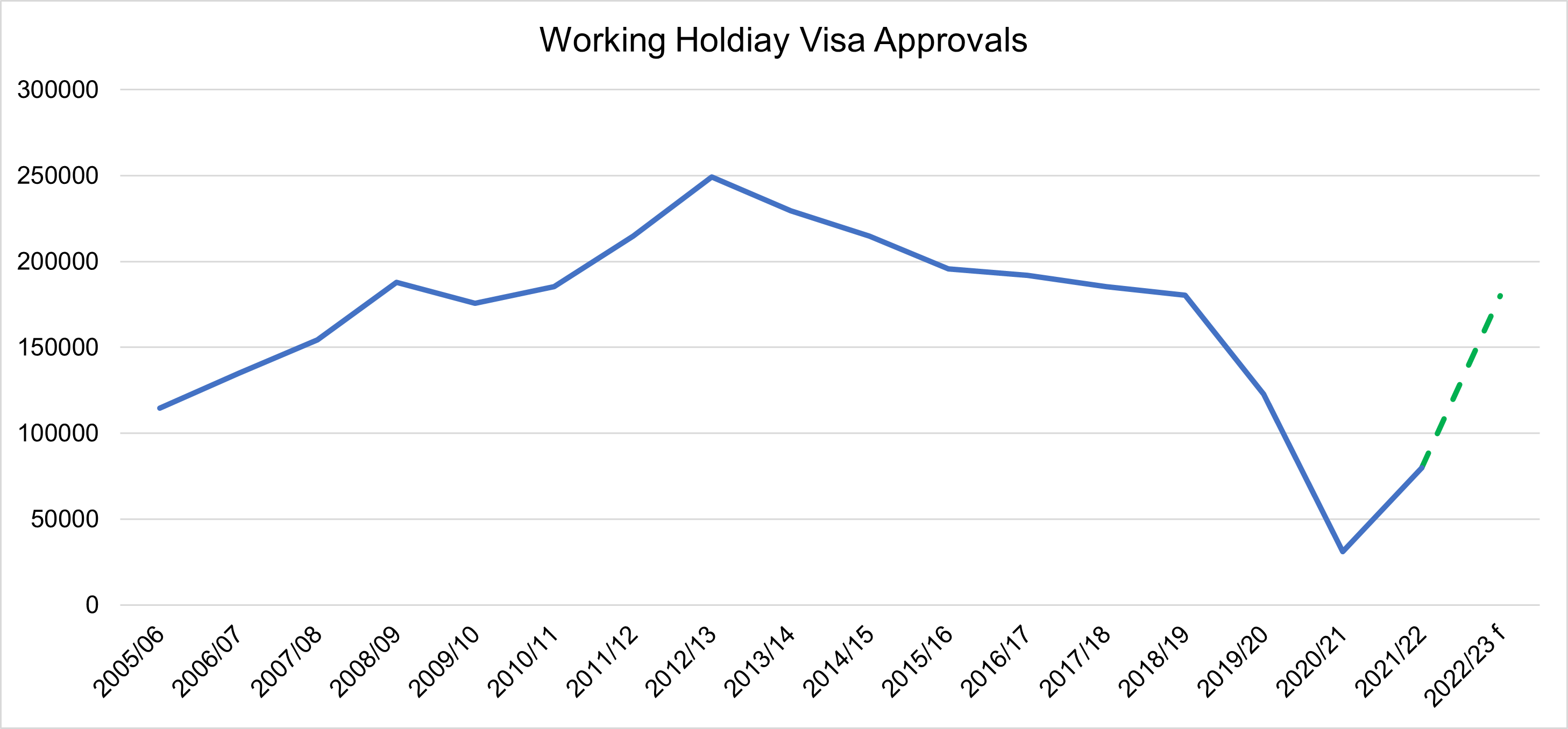

The other key cohort of international seasonal workers are backpackers. Their mobility adds another layer of value to the workforce. This is due to their ability to follow seasonal harvest periods right across the country. PALM workers are far less mobile in comparison. These working holiday visa approvals have jumped alongside the re-opening of borders. Despite the jump, the number of international arrivals utilising these visas remains below pre-COVID levels. Placing further pressure on seasonal labour is the trade agreement between Australia and the UK. The agreement is expected to come into effect in the back half of 2023. The FTA will remove the requirement for British backpackers to complete 88 days of farm work. British backpackers have had to complete farm work to extend their visa into a second year. This removal could drive a further shortfall of up to 10,000 backpackers from the seasonal workforce each year.

This was a key driver behind the decision to legislate a new Agricultural Visa back in 2021. Though a lack of interest from southeast Asian nations saw the program scrapped and rolled into the current PALM scheme. So, while the widening of the PALM scheme has helped to address supply gaps, the loss of British backpackers remains a real concern.

So, what else can be done to address these issues

The changes explored above provide a decent base to build upon. From this there are additional steps that will help to ensure a more resilient labour supply. Greater collaboration between government and industry bodies remains key. While further tweaking of the PALM scheme to enable greater flexibility of movement is also needed. Greater industry funding will also help to meet various skills shortages across sectors. Better working conditions and pay will also make the industry more attractive to local workers. While there is no silver bullet, these changes will help to ensure a more stable and sustainable supply of seasonal labour in the seasons to come.

Most Popular

Subscribe to insights today

Receive reports direct to your email by subscribing to Rural Bank Insights.